Parable of the Sower and South Africa: A mirror to our dystopian present

How Octavia Butler’s dystopian novel reflects South Africa’s present, and what we can do about it.

Okay, girlies, let’s talk about books today. I started reading Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler around the time of the US 2024 elections. Like many others, I was drawn to its predictions about the state of the world (ie the US of A) in 2025. But as I turned the pages, I couldn’t help but notice how closely the novel mirrors South Africa’s current realities. From privatized security to income inequality, Butler’s dystopian future feels uncomfortably familiar, and all I could think was “Ooooooohhhhh this is the bad place”. So, let’s dive into what this book means for us as South Africans and how we can use its lessons to navigate our challenges because things are very many.

Privatized security: gated communities and the “Undesirables”

The novel introduces us to Lauren Olamina, a young woman living in a gated community where security is privatized, and the “undesirables”; the poor, hungry, and desperate people, are kept out. Sound familiar? In South Africa, we’ve got our version of this: gated communities, road closures, and private security companies patrolling our neighborhoods. As Bénit-Gbaffou (2006) points out, these practices are often seen as “bad” forms of community policing, reminiscent of apartheid-era segregation.

But here’s the gag: it’s not just about race anymore. Income inequality plays a huge role. Think about how many middle-class Black families are now living behind walls and electric fences, paying for private security because the police can’t (or won’t) protect them. Lauren’s community sets up patrols to keep themselves safe, but she’s worried they’re not prepared for the day when the “undesirables” break through their walls and create devastation. She also has to deal with her stepbrother, Keith, who eventually leaves their compound and becomes involved in nefarious things which ultimately leads to his death, when he was 13. And then the day comes, her fears are realized: her father is killed, her neighborhood is burned to the ground taking with it her entire family, and she’s forced to flee.

Now, let’s be real, this isn’t just fiction. In Cape Town, you need to walk in the CBD and you’ll see the amount of homeless people on your way to trendy bars and restaurants. You don’t need to go to townships like Delft, KTC, and the Cape Flats where poverty and crime are rampant. We look through the homeless children who are addicted to drugs and resort to crime to survive as if this level of inequality is normal and not indicative of not only government failure, but also societal failure. How dystopian is that?

Hyper empathy: Seeing the poor as people

One of the most fascinating aspects of Lauren’s character is her hyperempathy, a condition that forces her to feel the pain of others. It’s described as being both a blessing and a curse. On one hand, it makes her deeply compassionate to the pain and suffering of others, if someone is hurt she feels the same hurt they feel. On the other, it’s exhausting because she can’t ignore the suffering around her and it is seen as a weakness. This got me thinking about how we, as South Africans, have become desensitized to poverty. We walk past homeless people sleeping on the streets, barely giving them a second glance. We expect poor people to be okay with scraps that even we wouldn’t accept but they should because they’re poor. Take for example the recent Mi Desk donation to Cape Town Schools by McDonald's, the idea is that primary school pupils will carry around these portable, solar-powered bags that also double as school desks according to Mcdonalds (24 January 2025). We expect these little 6-year-old children to bear the brunt of the failures of the Education Department, to provide adequate learning facilities to their learners and Eskoms failure to provide reliable electricity to the nation and more importantly, schools. We’ve stopped seeing poor people as people. Lauren’s hyper-empathy is a reminder that we need to reconnect with our humanity and see the poor not as “undesirables” but as people who deserve dignity and care.

Corporate Greed and Political Corruption: The DA, Oppenheimers, and the Rise of Fascism

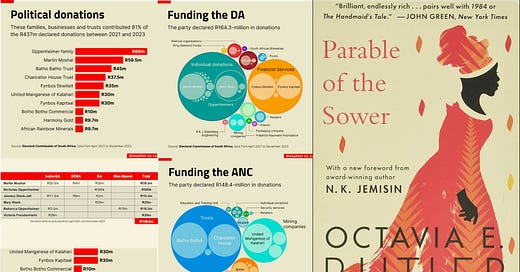

Now, let’s talk about the big bad: corporate greed and political corruption. In the book, unchecked corporate dominance leads to the privatization of essential services, such as water and security, exacerbating social inequalities. Sound familiar? In South Africa, we’ve got our version of this mess. Take the DA, for example. Did you know that during 2021/2022, 64% of their funding came from just two donors: Mary Oppenheimer Slack and Martin Moshal? And let’s not forget the foreign donors like the Friedrich Naumann Foundation and the Danish Liberal Democracy Program, who’ve poured millions into the party (My Vote Counts, 2023). Then there’s the Boerelegioen, a far-right group that’s been pushing the myth of “white genocide.” A judge even ruled that their claims were “not real” (Gerntholtz and Others v Pieterse N.O and Others, 2025). But these groups, along with apartheid-era billionaires like the Oppenheimers, continue to influence our political discourse, both locally and globally. To go back to the topic of McDonalds, they have partnered with the DA to clean up their image following global boycotts of the brand because of their decision to continuously fund and support the genocide of the people of Falasteen (Palestine).

The novel also warns of the dangers of fascist leaders who exploit fear and scapegoat vulnerable populations. In South Africa, we’ve seen the rise of right-wing rhetoric like the “white farmer genocide” and parties, often funded by the same corporate interests that benefit from our wealth and income inequalities.

World Disasters and the Scapegoating of the Poor

Climate change plays a major role in Parable of the Sower, causing food shortages, mass migration, and social unrest. The fascist leaders in the novel, like President Christopher Donner, respond to these crises not by addressing their root causes but by blaming the poor and pushing violent, exclusionary policies. This mirrors our reality. We have millions of refugee and asylum seekers that flock to South Africa, fleeing countries like Congo where there is a genocide of the Congolese people by the Rwandan and Western-backed M23 terrorists. As climate change worsens and the war machine wages on, we’re seeing more climate refugees, and people displaced by droughts, floods, and wars. But instead of treating them as victims, governments are fortifying borders and criminalizing migrants.

In South Africa, we’ve got our version of this with xenophobic attacks and the scapegoating of foreign nationals. Instead of strengthening our borders and dealing with the corruption that allows undocumented migrants to come into the country illegally through bribes, the identity fraud that comes from Home Affairs officials selling peoples' identities, etc we blame everything on people who are genuinely trying to just live. Instead of addressing these very real concerns, our Minister of Home Affairs, the DAs Leon Amos Schreiber, is busy acting like the Minister of Tourism Affairs of Cape Town working overtime to increase tourism to Cape Town like that’s the most pressing concern we have.

Earthseed Philosophy: Hope in community led solutions

Despite the grim realities, the book offers hope through the Earthseed philosophy, which emphasizes adaptability and community. Lauren believes that “God is change” and that it’s our responsibility to shape that change for the better. This theme resonates deeply with South African grassroots movements that are striving for social justice and environmental sustainability. From community gardens to neighborhood watches, these initiatives show us that our freedom won’t come from politicians or private entities, it will come from us, working together.

Love Your Community, Fight for Your Future

Mtase, Parable of the Sower isn’t just a warning, it’s a call to action. As South Africans, we must recognize the dangers of privatized security, corporate greed, and political corruption. But more importantly, we must turn to community-led solutions for a better future. So, the next time you walk past a homeless person or hear about another corporate scandal, remember Lauren’s words: “God is change.”

I would love to hear your thoughts on the book if you’ve read it, and any themes that you’ve picked up!

References

Bénit-Gbaffou, C. (2006). Police-Community Partnerships and Responses to Crime: Lessons from Yeoville and Observatory, Johannesburg. Urban Forum, 17(4), 301–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02681235

Carl Death. Popular politics and resistance movements in South Africa. Review of African Political Economy. 2011. Vol. 38(129):501-503. DOI: 10.1080/03056244.2011.598647

Gerntholtz and Others v Pieterse N.O and Others (3958/2023) [2025] ZAWCHC 51. Southern African Legal Information Institute. https://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZAWCHC/2025/51.h

Minnaar, A., & Pretorius, S. (2005). Who goes there?: Illegals in South Africa. Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology, 18(2), 45-60. https://journals.co.za/doi/10.10520/AJA0259188X_696

My Vote Counts. (2023). The 3 biggest funders behind political parties. https://myvotecounts.org.za/the-3-biggest-funders-behind-political-parties/

https://www.mcdonalds.co.za/news-notifications/mcdonalds-south-africa-empowering-young-learners-with-a-better-future

Mntase!!!! I love your writing. I haven't read the book but it's certainly on my DNF! Great article - its so disheartening witnessing the regress in basic humanity specially from our leaders and yet we're only 30 years into democracy.